Challenging Inaccessibility

How can we challenge inaccessibility?

Do you have a disability? Do you know someone who does? People with disabilities make up the largest minority population in the world. Anyone, no matter what age, race, gender or other categories of human diversity, can have or develop a disability.

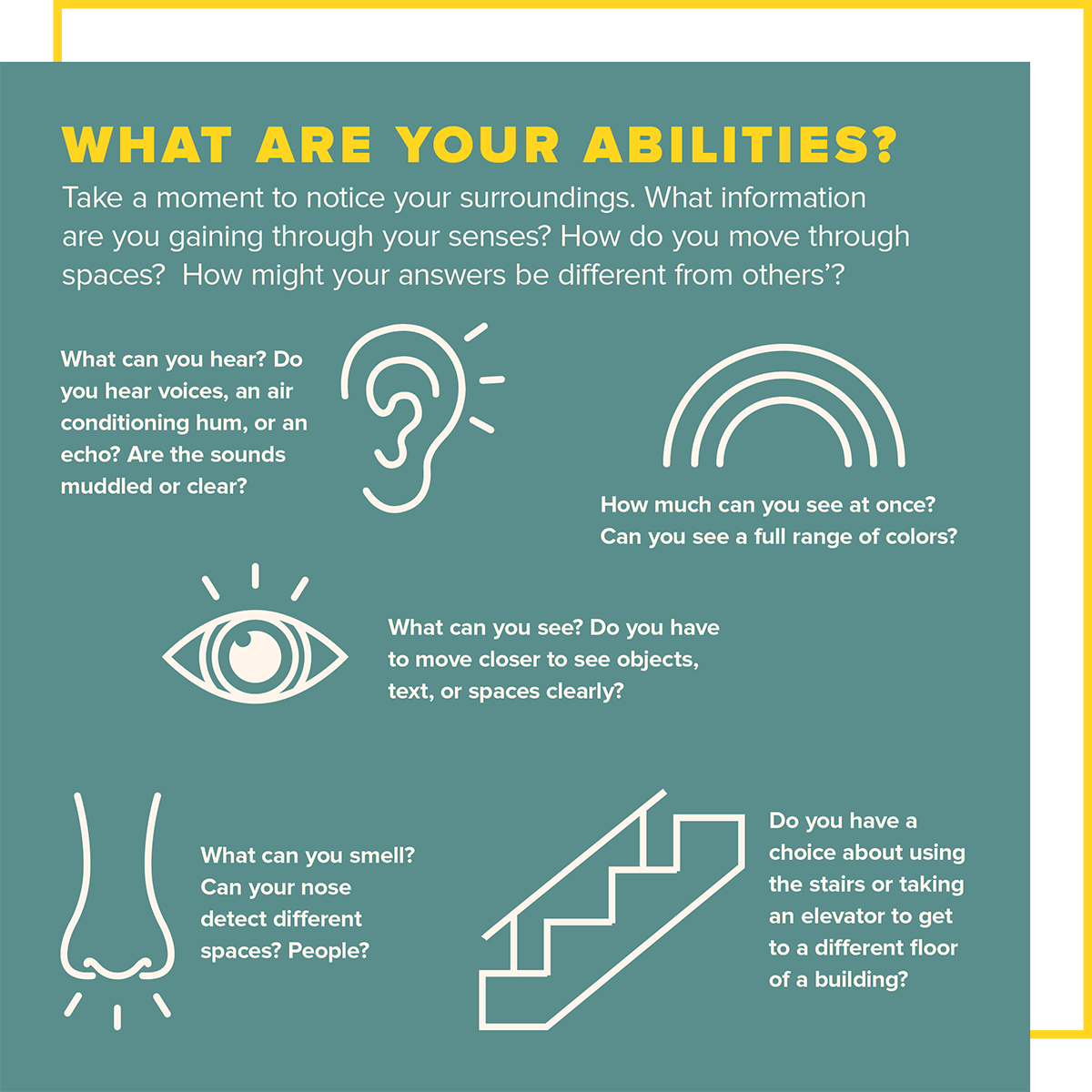

As we age, we will all develop one or more disabilities. In the United States, nearly one in five has a disability, and yet too many aspects of our society, legal system, and infrastructure remain inaccessible. For example, multi-story historic buildings are allowed to operate even though the lack of an elevator prevents those with physical mobility limitations from accessing all levels. Audio does not always come with captions, which means people with hearing disabilities cannot know that information. Online photographs often omit a caption or include the most basic description, which prevents those with sight limitations from knowing the image’s content. Those with disabilities are not excluded due to the way their bodies function but rather because of the ways these spaces have been designed.

Redefining Redefine/ABLE: From Access to Inclusion at the Peale

By Dr. Nancy Proctor

Pre-Covid-19, this essay began as a discussion of the way in which contemporary lives blur the boundaries between the “real” and the “virtual.” In our cross-platform world, my thesis went, we move between the physical and digital spheres like cyborgs: an encounter can be no less impactful, an emotion no less “real,” for having been experienced in an online environment. By the same token, there are few activities in the physical world that remain unmediated by digital tools, at minimum the ubiquitous “phone,” without which, it is easy to imagine, we would no longer have memories.

Ironically it took a global pandemic to reveal just how deeply rooted we still are in the physical world. By restricting us to online interactions for months on end, Covid-19 showed us how ill prepared we were to use our advanced digital technologies to their full potential, and where our digital blind spots lay. Even at the Peale, with a technologically-savvy team and a born-digital collection, we found ourselves in April 2020 wondering why we hadn’t been doing more online pre-quarantine, given the extraordinary increase in our global reach and audiences as we took all of our programs online for the duration of the pandemic. For example, the Peale now has a growing audience of Deaf participants in its online programs – an inclusive design development that was inspired the Redefine/ABLE exhibition’s move online and will continue into the Peale’s programming in the physical world as well. What took us so long?

As “the oldest new museum in Baltimore,” the Peale has embraced its unparalleled opportunity to question and reinvent the very concept of museum for the 21st century, while building on two centuries of cultural, technological, and educational innovation within its own historic walls. Opened in 1814 by artist Rembrandt Peale, Peale’s Baltimore Museum and Gallery of the Fine Art Arts was housed in the first purpose-built museum in the United States. Rembrandt’s museum was inspired by his father, Charles Willson Peale, who had opened the first American museum in Philadelphia in 1786. Rembrandt also introduced gas lighting to the city of Baltimore. By 1816 his Baltimore Gas Light Company was building the country’s first gas streetlight network, giving Baltimore its nickname today: “Light City.”